For a long time, while we often use phrases such as "selflessness", "giving" and “dedication"to pay tribute to our mothers, we may have greatly underestimated the huge cost associated with the role of a "mother".

Recently, the news of Bill and Melinda Gates’ divorce made headlines in major news outlets. Before this saga, Melinda had vividly described the difficulties faced by many mothers in an earlier interview:

"I like raising children, but in doing so, I am unable toparticipate inso-called productive work, as I will be very busy taking care of the children and changing their diapers. I would not be able to keep up with business news nor current developments. So, when someone raised a question during dinner, Bill would answer immediately and give a nearly perfect answer. That was when I realized that I hardly had my own voice."

How difficult is it to be a mother in modern society? This article aims to provide a rational analysis of this question from an economic perspective.

01 Continuous decline in the willingness of young women to give birth.

In fact, motherhood may not only disconnect females from society, butsignificantly impact their career development. Empirical research has shown that childbearing has profound implications for the personal career development and income for women. Even for women who have not yet given birth, future expectations of childbearing will impact their current career choices. Generally, the decrease in women’s willingness to give birth is largely due to its impact on career development.

Therefore, despite the implementation of the two-child policy since 2016, the National Bureau of Statistics of China has reported that the deregulation of the fertility policy did not significantly increase fertility rates.

The willingness of young people, especially young women, to have children is still declining. In 2014, most provinces have already allowed families with only one child to have a second child. However, by the end of 2015, less than 20% of single-child families filed applications to have a second child, which demonstrates the low willingness to have children (Wang et al., 2017).

02 The cost of child bearing for females

The cost of childbearing can be divided into direct and indirect costs.

In an agricultural society, the main investment required to raise a child is food. As long as the child has enough food, he will be able to work and earnincome.However, in modernsociety, there is increasing emphasis on “human capital”, which places intelligence above physical strength. The main way to accumulate human capital is through education and training, both of which can be costly. Especially in China, limited educational resources has also increased the competition between families to raise their children.

At present, the labor participation rate of women is around 70% in China. With the increase in labor participation rate and corresponding rewards from labor, this has also resulted in an increase in opportunity cost of childbearing. Thus, it has become difficult for women to forsake job opportunities due to childbirth.

In the United States, the annual income and wages of women are highly correlated with the age they give birth to a child. For each additional year that they take to give birth to a child, their annual income increases by an average of 9%, wages increase by an average of 3%, and working hours increase by an average of 6% (Miller, 2011). In China, wages drop by 7% for every additional child that a woman gives birth to (Yu Jia and Xie Yu, 2014). The cost of having a child in Germany is 35% of the mother’s total income, and ¾ of the implications comes from the decrease in labor supply and ¼ comes from the decrease in wages. At the age of 20, the income of women who had given birth was 5% higher than that of women who had not given birth; at the age of 40, however, the income of women who had not given birth was 10% higher than that of women of the same age. (Adda et al., 2017).

This difference may be caused by careerinterruptiondue to having children, or due to women with different educational backgrounds and different income levels having different willingness to bear children. For example, women with higher incomes have greater opportunity costs of giving birth, thus explaining their lower willingness to give birth.

Therefore, the ideal experimental design is to compare two groups of women with the same educational background and income level, with the only difference being that one group of women has given birth to children, and the other group has never given birth. Another paper published in the "American Economic Review" compared the data of more than 30,000 women who received IVF in 10 years to compare the impact of having a baby on the occupation of women.

In this set-up, the income, education level, and labor participation rate of these women before IVF are all highly similar. Hence, the researchers compared the differences in the workplace performance of the two groups of women after successful treatment (becoming a mother) and unsuccessful treatment (not becoming a mother).

The research shows that motherhood has a continuous negative impact on women’s professional performance. Within 2-5 years after giving birth, their income decreased by 12% (Lundborg et al., 2017).

03 What can we do to improve the situation?

The reasons have explained the decrease in willingness of childbearing for women, where there is a high opportunity cost of giving birth and raising children. As the cost of raising a child increase, families will have fewer children to maximize utility, and fertility rate thus decreases. In addition to the direct cost of raising children, the time spent and the opportunity cost of raising a child further hinders the increase in fertility rate.

One way to improve the situation is to provide childbirth tax cuts or subsidies. As raising a child is expected to be costly, Professor Zhizhang Wang of Southwest University estimated the total direct and indirect costs of a second child from pregnancy to graduation in the "Second Child Basic Cost Estimation and Social Sharing Mechanism Research (2017).” The research found out that the cost of raising a child is 870,000 RMB in first-tier cities (Guangzhou), 730,000 RMB in second-tier cities (Chongqing and Wuhan), 500,000 RMB in third-tier cities (Nanchang and Weifang), and 400,000 RMB in fourth-tier cities (Yuxi). Thus, the cost of parenting is a relatively large expenditure for ordinary families. On the other hand, as the entire society benefits from the demographic dividend brought by the increase in newborns, we should provide appropriate tax cuts or subsidies for marriage and childbearing families.

The second method is to provide childcare services. In 2019, China’s fertility rate bottomed out, where total fertility rate of first-tier cities such as Beijing is below 1 - far less than the international average. Recently, not having children has become the trend of the younger generation. According to the survey, the main reason is that the cost of raising children is too high for most people. In addition, mothers are often assumed to be responsible for parenting after giving birth. Therefore, including kindergarten education in the compulsory education system can reduce the necessary time expenditure for parents and share the burden of raising children, which may reduce the cost of parenting and increase women's willingness to bear children.

The third is to extend parental leave. In other countries, parental leave includes maternity leave for women, paternity leave for men, and parental leave for both parents. In comparison, China’s paternal leave system is mostly concentrated on women. The establishment of paternity leave can reduce the physical and mental stress of wives during childbirth and allow both parents to take care of the newborn at the same time. In addition, this helps to reduce the social discrimination against women in employment, reduce the burden of childbirth on women, and balance the impact of gender differences in the labor force.

Helping women to reduce childbirth costs and creating a more equal working environment will be the best gift that society can provide for all mothers.

Reference

Amalia Miller (2011) “The effect of motherhood timing on career path”,Journal of Population Economics, Vol 24, No.3, 1071-1100

Jerome Adda, Christian Dustmann, and Katrien Stevens (2017) “The Career Costs of Children”,Journal of Political Economy,Vol. 125, issue 2, 293 – 337

Lundborg, P., Plug, E. P., Wurtz Rasmussen, A., Department of Economics, Lund University, Nationalekonomiska institutionen, & Lunds universitet. (2017). “Can women have children and a career: IV evidence from IVF treatments”,American Economic Review, 107(6), 1611-1637.

Wang, Fei, Liqiu Zhao, and Zhong Zhao (2017), "China's family planning policies and their labor market consequences",Journal of Population Economics, 30:31-68.

於嘉和谢宇(2014) “生育对我国女性工资率的影响”, 人口研究,第38卷,第1期,第18-29页

金李:如何让年轻人敢生娃?这里有4份提案@全国两会

About the Authors

Dr. Hui Wang is an Associate Professor of Applied Economics at the Guanghua School of Management (GSM), Peking University. He is the associate director and research fellow of the Institute of Economic Policy Research of Peking University (IEPR-PKU). He is one of the first “Richu Dongfang – Guanghua” Research Fellows. Dr. Hui Wang holds a Ph.D. and a master’s degree in economics from University of Toronto.

Dr. Hui Wang’s research interests include Industrial Organization, Labor Economics, Economic Development, and Applied Econometrics. He has published papers in prestigious journal in Economics such as Journal of Political Economy, RAND Journal of Economics, International Economic Review, and Journal of Population Economics.

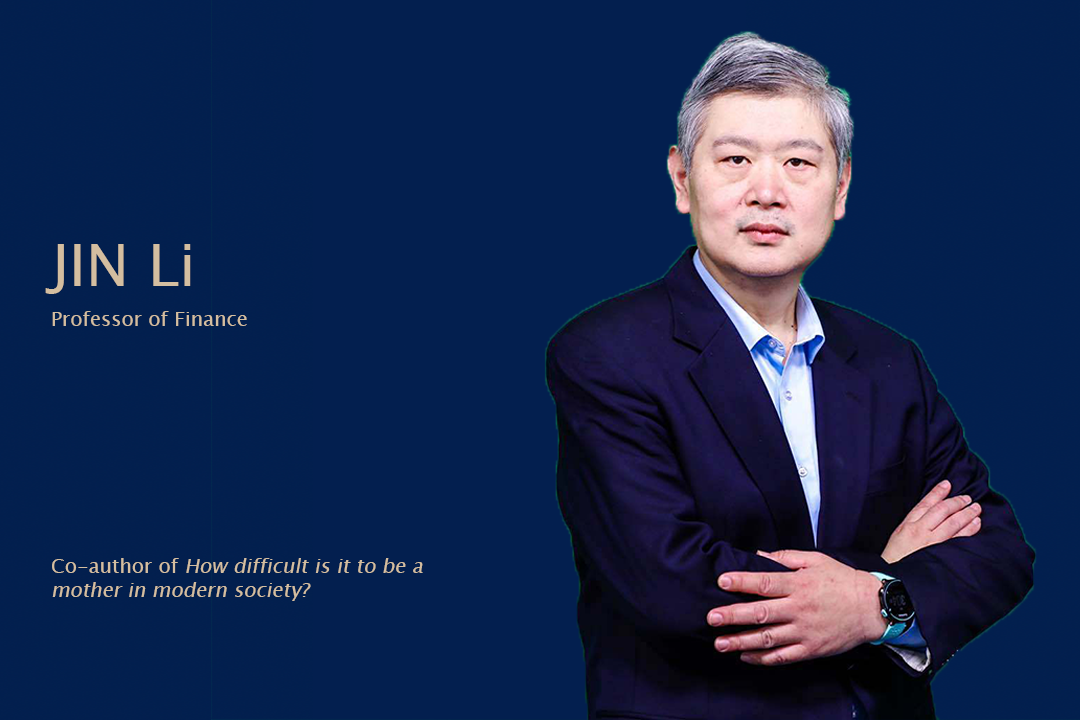

Dr. Li Jin currently serves as Chair Professor of Finance at Peking University. He is the Associate Division Head of the Division of Economics and Management at Peking University, and Director of the National Centre for Financial Research at Peking University. Before joining PKU, he was a finance professor at the Harvard Business School and at the University of Oxford Saïd Business School.

Li Jin currently serves as the Vice Chairman of the Board of the Chinese Management Science Society, and Director of its Financial Management Special Committee, and Vice Chairman of the Advisory Board of Chinese Academy of Management, and Director of the Private Equity Society. He is also an internationally recognized expert of corporate governance and serves on the board and scientific committee of Global Corporate Governance Colloquia representing China. He has been serving as the director and senior advisor of many academic and practitioner organizations around the world, and the independent director or outside director for many listed and non-listed firms, fund management companies and SEOs in China and abroad. He also serves as the senior counselor or advisor in several academic and practical institutions domestic and overseas.

Programs

Programs